Author: André Wiss

Europe has a big problem: reaction.

Do not get me wrong, the EU can be proactive as it showed in the case of introducing USB-C as the new standard charger cable norm in Europe. However, in most really relevant areas the EU is sluggish, divided and only re-acts to trends and emergencies.

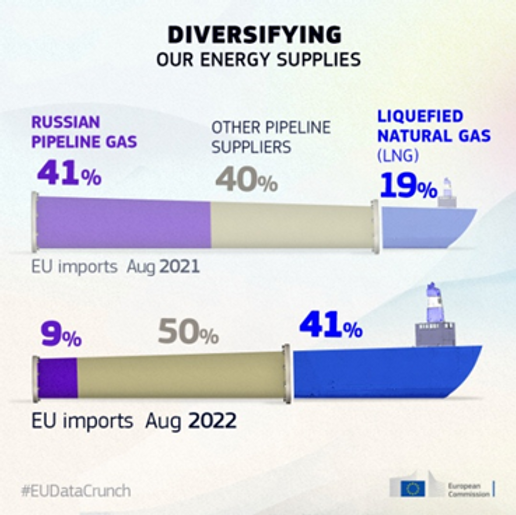

The European Commission’s graph on the shift in the percentage of how gas comes into the EU is telling. On the one hand, it is a success in terms of how much less gas is coming from Russia, however, it does not show how much less energy supplies are coming in overall. Like Covid, the Russian war on Ukraine has laid bare the weaknesses of a (not so) United Europe. The title of this Op-ed should be EU reaction instead of EU action. Let me take you back two years. In 2020, in the wake of the Covid pandemic, we saw a panicked return to individual national sovereignty and a temporary de-facto suspension of the Schengen Treaty whilst the European Commission battled to coordinate a joint effort to react to the financial disaster caused by the pandemic-induced lockdowns. Now, in 2022, we have been treated to the first inner-European war since the partition of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, causing an energy crisis that should have been much more predictable and preventable than the Covid-19 pandemic. Neither looks good for the EU when beheld in the cold light of day. The energy crisis facing Europe is the result of three factors that came together to create a perfect storm. 1) President Putin of Russia decided it was a “good time” to finish the job he felt he had left unfinished in 2014, 2) the completely divergent energy strategies among EU member states blew up in their faces and 3) the accelerating climate change did reveal a further threat to Europe’s energy security. Of course, these and other factors are closely intertwined, but the EU cannot be blamed for all of them. To be more precise: Russia is an external factor and whilst some opportunities of integrating Russia more into Europe were missed in the 1990s and early 2000s the EU cannot be blamed for Russia’s evidently ill-judged and illegal invasion of Ukraine. The reason why the EU’s energy supply is so badly affected by the war in Ukraine have much more to do with a lack of strategy and cooperation than with the war as such. Also, whilst the response to the waves of Ukrainian refugees has been exemplary so far and created a show of unity among EU member states the energy crisis is a different matter. Where to start?! Just looking at the two main European actors is very revealing. Germany: Against its better knowledge, Germany decided to rely heavily on and even enhance its gas supply from Russia with the building of the Nordstream2 pipeline. This is particularly startling given that Germany kept pursuing this course subsequent to Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. Despite its vociferous support for carbon-neutrality Germany also insisted on the classification of gas-driven power stations as renewable. France: the French Republic has consistently hedged its bets on nuclear energy, which, prima facie, has a low carbon footprint and has provided its citizens with cheap electric heating for decades. It also successfully lobbied to have it included on the Commission’s list of renewable energies that benefit from the investment as part of the Green New Deal. Poland and Romania also heavily rely on nuclear power. Germany phased out nuclear power because of the weight and influence its Green Party has been able to attain in politics. The German Green Party started to gain momentum in the 1980s with an anti-nuclear agenda. Regarding nuclear energy, like in other fields such as euthanasia and pre-natal diagnostics, Germany has “exported” ethical problems to the surrounding EU countries.

Now, on top of all this, the summer of 2022 has exposed a further liability that cannot be so easily fixed as importing liquid gas from North America to make up for the shortcomings resulting from the war in Ukraine: exacerbated climate change. In the summer of 2022 the heat and drought wave that raised the temperature of Europe’s rivers and lowered their water levels unbearably imperiled the hydroelectric and nuclear power supply in Europe, forcing, e.g. France, to reduce the output of its nuclear power stations because the warm river water could no longer sufficiently cool the cycle.

Now, these are just a few examples of how there is no common energy policy in the EU, despite the Commission trying to develop one. The member states were supposed to deliver their individual energy strategies to the Commission by 2020. Still, the feedback was only completed in September 2022, half a year into the Russian war on Ukraine. The Green New Deal is crucial and the Commission is doing its best to work for better energy security. However, the elephant in the room remains that the EU Commission and Parliament have (contrary to the popular narrative) far too little power in all relevant matters and are hampered by the unanimity voting requirement in the EU Council. If the EU wants to be a global player in the energy sector and any other field for that matter its member states need to empower the relevant EU institutions to be able to tackle Europe’s energy strategy head-on and in a proactive way. Otherwise, they are the ones who condemn the EU to be an expensive and ineffective semi-supranational organisation.